Rain Gear Advice for Olympic National Park in Summer UPDATED

Rain Gear Advice for Olympic National Park in Summer

| Olympic National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN category 2 (national park) | |

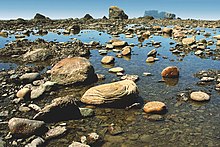

Cedar Creek and Abbey Island from Reddish Beach | |

| Location in Washington Show map of Washington (land) Location in the United States Show map of the U.s. | |

| Location | Jefferson, Clallam, Mason, and Grays Harbor counties, Washington, Usa |

| Nearest city | Port Angeles |

| Coordinates | 47°58′ten″N 123°29′55″West / 47.96935°N 123.49856°W / 47.96935; -123.49856 Coordinates: 47°58′10″N 123°29′55″W / 47.96935°N 123.49856°Due west / 47.96935; -123.49856 |

| Area | 922,650 acres (3,733.8 km2)[i] |

| Established | June 29, 1938 |

| Visitors | 2,499,177 (in 2020)[2] |

| Governing torso | National Park Service |

| Website | Olympic National Park |

| UNESCO Earth Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, nine |

| Reference | 151 |

| Inscription | 1981 (5th Session) |

Olympic National Park is a The states national park located in the State of Washington, on the Olympic Peninsula.[3] The park has four regions: the Pacific coastline, alpine areas, the west-side temperate rainforest, and the forests of the drier eastward side.[4] Inside the park in that location are three distinct ecosystems, including subalpine wood and wildflower meadow, temperate forest, and the rugged Pacific declension.[5]

President Theodore Roosevelt originally designated the park as Mountain Olympus National Monument on March 2, 1909.[half dozen] [seven] The monument was re-designated a national park by Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 29, 1938. In 1976, Olympic National Park was designated by UNESCO as an International Biosphere Reserve, and in 1981 every bit a World Heritage Site. In 1988, Congress designated 95 percent of the park (1,370 square miles (3,500 kmii)) as the Olympic Wilderness,[8] [nine] which was renamed Daniel J. Evans Wilderness in honor of Governor and U.South. Senator Daniel J. Evans in 2017.[10] During his tenure in the Senate, Evans co-sponsored the 1988 nib that created the country's wilderness areas.[11] Information technology is the largest wilderness surface area in Washington.

Park purpose [edit]

Equally stated in the foundation document:[12]

The purpose of Olympic National Park is to preserve for the benefit, use, and enjoyment of the people, a large wilderness park containing the finest sample of primeval forest of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, Douglas fir, and western red cedar in the entire U.s.; to provide suitable winter range and permanent protection for the herds of native Roosevelt elk and other wild animals indigenous to the area; to conserve and return available to the people, for recreational use, this outstanding mountainous land, containing numerous glaciers and perpetual snow fields, and a portion of the surrounding verdant forests together with a narrow strip along the beautiful Washington coast.

Natural and geologic history [edit]

Coastline [edit]

The coastal portion of the park is a rugged, sandy beach along with a strip of adjacent wood. It is 60 miles (97 km) long but simply a few miles wide, with native communities at the mouths of 2 rivers. The Hoh River has the Hoh people and at the town of La Push at the mouth of the Quileute River alive the Quileute.[13]

The beach has unbroken stretches of wilderness ranging from 10 to 20 miles (sixteen to 32 km). While some beaches are primarily sand, others are covered with heavy rock and very large boulders. Bushy overgrowth, slippery basis, tides and misty pelting wood weather all hinder foot travel. The coastal strip is more readily accessible than the interior of the Olympics; due to the hard terrain, very few backpackers venture beyond casual day-hiking distances.[ citation needed ]

The most pop piece of the littoral strip is the 9-mile (fourteen km) Ozette Loop. The Park Service runs a registration and reservation program to control usage levels of this area. From the trailhead at Ozette Lake, a 3-mile (four.8 km) leg of the trail is a boardwalk-enhanced path through nigh central coastal cedar swamp. Arriving at the ocean, information technology is a 3-mile walk supplemented by headland trails for loftier tides. This area has traditionally been favored by the Makah from Neah Bay. The third iii-mile leg is enabled by a boardwalk which has enhanced the loop's visitor numbers.[ citation needed ]

There are thick groves of trees adjacent to the sand, which results in chunks of timber from fallen trees on the beach. The mostly unaltered Hoh River, toward the south end of the park, discharges large amounts of naturally eroded timber and other migrate, which moves north, enriching the beaches. Even today driftwood deposits form a commanding presence, biologically as well equally visually, giving a gustation of the original condition of the beach viewable to some extent in early photos. Drift-material often comes from a considerable distance; the Columbia River formerly contributed huge amounts to the Northwest Pacific coasts.

The smaller coastal portion of the park is separated from the larger, inland portion. President Franklin D. Roosevelt originally had supported connecting them with a continuous strip of park land.

A 3D computer-generated aerial view

The park is known for its unique turbidites. Information technology has very exposed turbidities with white calcite veins. Turbidites are rocks or sediments that travel into the ocean as suspended particles in the flow of water, causing a sedimentary layering effect on the bounding main floor. Over fourth dimension the sediments and rock compact and the procedure repeats as a constant cycle. The park also is known for its tectonic mélanges that take been deemed 'smell rocks' by the locals due to its stiff petroleum odor. Mélanges are large individual rocks that are large plenty that they are deemed for in map drawings. The Olympic mélanges can exist equally large equally a business firm.

Glaciated mountains [edit]

Within the center of Olympic National Park rise the Olympic Mountains whose sides and ridgelines are topped with massive, ancient glaciers. The mountains themselves are products of accretionary wedge uplifting related to the Juan De Fuca Plate subduction zone. The geologic composition is a curious mélange of basaltic and oceanic sedimentary stone. The western half of the range is dominated by the tiptop of Mount Olympus, which rises to seven,965 anxiety (2,428 m). Mount Olympus receives a large amount of snow, and consequently has the greatest glaciation of any non-volcanic peak in the contiguous U.s.a. outside of the North Cascades. It has several glaciers, the largest of which is Hoh Glacier at 3.06 miles (4.93 km) in length. Looking to the east, the range becomes much drier due to the rain shadow of the western mountains. Here, in that location are numerous high peaks and craggy ridges. The tallest summit of this area is Mount Deception, at 7,788 anxiety (2,374 m).

Temperate rainforest [edit]

The western side of the park is mantled by temperate rainforests, including the Hoh Rainforest and Quinault Rainforest, which receive annual precipitation of about 150 inches (380 cm), making this possibly the wettest area in the continental United States (however, parts of the island of Kauai, such as the summit of Mountain Waiʻaleʻale, in the country of Hawaii receive more rain).[14]

As opposed to tropical rainforests and most other temperate rainforest regions, the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest are dominated by coniferous copse, including Sitka Spruce, Western Hemlock, Coast Douglas-fir and Western redcedar. Mosses coat the bark of these copse and even drip down from their branches in green, moist tendrils.

Valleys on the eastern side of the park also have notable old-growth woods, merely the climate is notably drier. Sitka Spruce is absent-minded, trees on boilerplate are somewhat smaller, and undergrowth is generally less dense and different in character. Immediately northeast of the park is a rather modest rainshadow surface area where annual precipitation averages most 16 inches.[xv]

Ecology [edit]

Co-ordinate to the A. W. Kuchler U.South. Potential natural vegetation Types, Olympic National Park encompasses v classifications: Tall Meadows & Barren, aka Alpine tundra (52) potential vegetation blazon with an Alpine Meadow (xi) potential vegetation form; a Fir/Hemlock (iv) vegetation type with a Pacific Northwest conifer woods (1) vegetation form; a cedar/hemlock/Douglas fir vegetation type with a Pacific Northwest conifer wood (1) vegetation form; Western spruce/fir vegetation blazon (xv) with a Rocky Mount conifer forest (3) vegetation course; and a bandbox/cedar/hemlock (1) vegetation blazon with a Pacific Northwest conifer forest (1) vegetation course.[sixteen]

Because the park sits on an isolated peninsula, with a high mountain range dividing information technology from the state to the south, it adult many endemic found and animal species (like the Olympic Marmot, Piper's bellflower and Flett's violet). The southwestern coastline of the Olympic Peninsula is besides the northernmost non-glaciated region on the Pacific coast of N America, with the result that – aided by the distance from peaks to the coast at the Terminal Glacial Maximum existence almost twice what it is today – it served as a refuge from which plants colonized glaciated regions to the north.

The park also provides habitat for many species (like the Roosevelt elk) that are native only to the Pacific Northwest coast. As a result, scientists have declared it a biological reserve and study its unique species to meliorate empathize how plants and animals evolve. The park is domicile to sizable populations of black bears and black-tailed deer. The park also has a noteworthy cougar population, numbering about 150.[17] Mount goats were accidentally introduced into the park into the 1920s and have acquired much damage on the native flora. The NPS has activated management plans to control the goats.[18] The park contains an estimated 366,000 acres (572 sq mi; 1,480 km2) of old-growth forests.[19]

Wood fires are exceptional in the rainforests of the park'south western side; however, a severe drought later on the driest jump in 100 years, coupled with an extremely low snowpack from the preceding wintertime, resulted in a rare rainforest fire in the summer of 2015.[20]

Ecological zones - glaciated mountains, subalpine forests and meadows, temperate rainforests, and coastline

Climate [edit]

According to the Köppen climate nomenclature system, Olympic National Park encompasses two classifications: a temperate oceanic climate (Cfb) in the western half, and a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb) in the eastern one-half.[ commendation needed ] Co-ordinate to the United States Department of Agriculture, the plant hardiness zone at Hoh Rainforest Visitor Center is 8a with an boilerplate annual farthermost minimum temperature of xiv.5 °F (−nine.seven °C).[21]

| Climate data for Elwha Ranger Station, 1948-2006 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | December | Yr |

| Record high °F (°C) | 64 (xviii) | 67 (19) | 69 (21) | 78 (26) | 87 (31) | 93 (34) | 96 (36) | 97 (36) | 91 (33) | 76 (24) | 70 (21) | 65 (eighteen) | 97 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40.vii (4.8) | 44.9 (seven.2) | l.3 (10.2) | 56.9 (thirteen.8) | 63.v (17.5) | 68.ane (20.one) | 73.8 (23.2) | 74.1 (23.4) | 68.5 (20.3) | 56.9 (13.viii) | 46.4 (8.0) | 42.0 (5.6) | 57.2 (14.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.1 (−0.5) | 32.3 (0.2) | 34.i (1.ii) | 37.iii (two.9) | 42.0 (5.vi) | 46.half-dozen (eight.1) | 49.9 (nine.9) | 50.9 (10.v) | 47.five (8.6) | 41.1 (5.1) | 35.7 (two.1) | 32.7 (0.four) | twoscore.i (four.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | ii (−17) | viii (−xiii) | 15 (−nine) | 26 (−3) | 29 (−2) | 32 (0) | 36 (two) | 36 (2) | 32 (0) | 21 (−6) | 10 (−12) | 8 (−13) | 2 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 9.02 (229) | 6.xc (175) | 6.02 (153) | 3.27 (83) | i.84 (47) | ane.20 (30) | 0.75 (nineteen) | ane.21 (31) | 1.77 (45) | 5.27 (134) | 9.17 (233) | 9.88 (251) | 56.3 (1,430) |

| Boilerplate snowfall inches (cm) | 7.one (18) | 2.0 (5.1) | 1.2 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | i.ane (ii.8) | 3.1 (seven.9) | 14.5 (36.8) |

| Boilerplate precipitation days (≥ .01 in) | 17 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 11 | ix | five | 6 | viii | fourteen | xviii | 17 | 149 |

| Source: "ELWHA RANGER STN, WASHINGTON". Western Regional Climate Middle. | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Hoh Rainforest Visitor Center (elevation: 745 ft / 227 m), 1981-2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calendar month | Jan | February | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | November | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 44.vii (seven.1) | 47.9 (viii.8) | 51.4 (x.eight) | 55.8 (xiii.2) | 61.eight (16.6) | 65.4 (xviii.6) | lxx.8 (21.6) | 72.2 (22.3) | 67.4 (19.vii) | 58.8 (fourteen.9) | 48.9 (9.4) | 43.9 (6.half-dozen) | 57.5 (14.two) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 39.8 (4.3) | 41.2 (v.ane) | 43.five (half dozen.4) | 46.8 (viii.2) | 52.1 (xi.2) | 56.1 (xiii.four) | 60.5 (15.8) | 61.3 (16.3) | 57.5 (14.2) | 50.8 (10.iv) | 43.2 (6.ii) | 38.eight (3.8) | 49.3 (9.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 34.8 (i.6) | 34.4 (1.3) | 35.6 (2.0) | 37.8 (iii.2) | 42.iv (v.8) | 46.eight (8.2) | 50.1 (10.1) | 50.5 (10.3) | 47.half dozen (8.seven) | 42.vii (v.nine) | 37.6 (iii.1) | 33.viii (1.0) | 41.2 (v.1) |

| Average atmospheric precipitation inches (mm) | 20.59 (523) | 14.45 (367) | 14.78 (375) | 10.lx (269) | 6.39 (162) | four.68 (119) | 2.16 (55) | 2.76 (lxx) | four.15 (105) | 13.11 (333) | 22.55 (573) | xix.07 (484) | 135.29 (3,436) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.1 | 76.0 | 76.8 | 74.1 | 71.9 | 73.9 | 68.8 | 69.9 | 69.0 | 74.2 | 83.0 | 83.1 | 75.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 35.7 (2.1) | 34.two (1.two) | 36.seven (2.half dozen) | 39.0 (iii.nine) | 43.iii (6.3) | 47.ix (8.8) | 50.2 (10.1) | 51.4 (ten.viii) | 47.4 (eight.6) | 42.9 (six.one) | 38.4 (iii.6) | 34.1 (1.2) | 41.8 (5.4) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[22] | |||||||||||||

Human history [edit]

Prior to the influx of European settlers, Olympic'southward human being population consisted of Native Americans, whose use of the peninsula was idea to take consisted mainly of fishing and hunting. However, contempo reviews of the record[ citation needed ], coupled with systematic archaeological surveys of the mountains (Olympic and other Northwest ranges) are pointing to much more than extensive tribal use of peculiarly the subalpine meadows than seemed formerly to exist the example. Most if non all Pacific Northwest indigenous cultures were adversely affected by European diseases (oftentimes decimated) and other factors, well before ethnographers, business operations and settlers arrived in the region, so what they saw and recorded was a much-reduced native culture-base of operations. Large numbers of cultural sites are at present identified in the Olympic mountains, and important artifacts have been institute.

When settlers began to announced, extractive industry in the Pacific Northwest was on the rising, peculiarly in regards to the harvesting of timber, which began heavily in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Public dissent against logging began to take hold in the 1920s, when people got their starting time glimpses of the lucent hillsides. This period saw an explosion of people's interest in the outdoors; with the growing use of the automobile, people took to touring previously remote places like the Olympic Peninsula.

The formal record of a proposal for a new national park on the Olympic Peninsula begins with the expeditions of well-known figures Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil and Gauge James Wickersham, during the 1890s. These notables met in the Olympic wilderness while exploring, and after combined their political efforts to accept the area placed inside some protected status. On February 22, 1897, President Grover Cleveland created the Olympic Woods Reserve, which became Olympic National Woods in 1907.[23] Following unsuccessful efforts in the Washington State Legislature to further protect the area in the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt created Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909, primarily to protect the subalpine calving grounds and summer range of the Roosevelt elk herds native to the Olympics.

Public desire for preservation of some of the area grew until President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a bill creating a national park in 1938. The Civilian Conservation Corps constructed a headquarters in 1939 with funds from the Public Works Administration. It is now on the National Register of Historic Places.[24] The national park was expanded past 47,753 acres (19,325 ha) in 1953 to include the Pacific coastline between the Queets and Hoh rivers, as well as portions of the Queets and Bogachiel valleys.[25]

Even after ONP was declared a park, though, illegal logging continued in the park, and political battles go on to this day over the incredibly valuable timber contained within its boundaries. Logging continues on the Olympic Peninsula, simply not within the park.[26]

Creature [edit]

Animals that inhabit this national park are chipmunks, squirrels, skunks, 6 species of bats, weasels, coyotes, muskrats, fishers, river otters, beavers, ruddy foxes, mountain goats, martens, bobcats, black bears, Canadian lynxes, moles, snowshoe hares, shrews, and cougars. Whales, dolphins, sea lions, seals, and sea otters swim about this park offshore. Birds that wing in this park including raptors are Wintertime wrens, and Canada jays, Hammond's flycatchers, Wilson's warblers, Blue Grouses, Pine siskins, ravens, spotted owls, Red-breasted nuthatches, Golden-crowned kinglets, Chestnut-backed chickadees, Swainson'southward thrushes, Red crossbills, Hermit thrushes, Olive-sided flycatchers, bald eagles, Western tanagers, Northern pygmy owls, Townsend's warblers, Townsend's solitaires, Vaux's swifts, band-tailed pigeons, and evening grosbeaks.

Recreation [edit]

There are several roads in the park, only none penetrate far into the interior. The park features a network of hiking trails, although the size and remoteness ways that it will usually have more than than a weekend to become to the high country in the interior. The sights of the pelting forest, with plants run anarchism and dozens of hues of green, are well worth the possibility of rain quondam during the trip, although July, August and September frequently accept long dry spells.

An unusual feature of ONP is the opportunity for backpacking along the beach. The length of the coastline in the park is sufficient for multi-day trips, with the entire day spent walking along the beach. Although idyllic compared to toiling upwards a mountainside (Seven Lakes Bowl is a notable example), one must be aware of the tide; at the narrowest parts of the beaches, high tide washes upwardly to the cliffs behind, blocking passage. There are besides several promontories that must be struggled over, using a combination of muddy steep trail and fixed ropes.

During winter, the viewpoint known equally Hurricane Ridge offers numerous wintertime sports activities. The Hurricane Ridge Wintertime Sports Club operates Hurricane Ridge Ski and Snowboard Area, a non for turn a profit alpine ski area which offers ski lessons, rentals, and cheap lift tickets. The small alpine expanse is serviced by ii rope tows and 1 poma lift. A large corporeality of backcountry terrain is accessible for skiers, snowboarders, and other backcountry travelers when the Hurricane Ridge Road is open. Wintertime access to the Hurricane Ridge Route is currently limited to Friday through Dominicus weather permitting. The Hurricane Ridge Winter Admission Coalition is a customs effort to restore seven-day-a-calendar week access via the Hurricane Ridge Road (the only park road accessing tall terrain in winter).

Rafting is available on both the Elwha and Hoh Rivers. Boating is mutual on Ozette Lake, Lake Crescent, and Lake Quinault.[ citation needed ] Fishing is allowed in the Ozette River, Queets River (beneath Tshletshy Creek), Hoh River, Quinault River (below North Shore Quinault River Bridge), Quillayute River and Dickey River.[27] A angling license is not required to fish in the park. Fishing for bull trout and Dolly Varden is not allowed and must be released if incidentally caught.[28]

Panoramic view from near the Hurricane Ridge visitor middle which is to the right

Views of the Olympic National Park tin exist seen from the Hurricane Ridge viewpoint. The road leading west from the Hurricane Ridge company centre has several picnic areas and trail heads. A paved trail called the Hurricane Loma trail is about 1.6 miles (2.6 km) long each manner, with an height gain of almost 700 feet (210 m). Information technology is not uncommon to observe snow on the trails even as late as July. Several other dirt trails of varying distances and difficulty levels co-operative off of the Hurricane hill trail. The picnic areas are open up only in the summer, and take restrooms, water and paved admission to picnic tables.

The Hurricane Ridge company center has an information desk-bound, gift shop, restrooms, and a snack bar. The exhibits in the company centre are open up daily.

A foggy day at Hurricane Ridge, every bit seen from the visitor heart

Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project [edit]

The Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project is the second largest ecosystem restoration project in the history of the National Park Service subsequently the Everglades. Information technology consisted of removing the 210-foot (64 k) Glines Canyon Dam and draining its reservoir, Lake Mills and removing the 108-pes (33 thou) Elwha Dam and its reservoir Lake Aldwell from the Elwha River. Upon removal, the park will revegetate the slopes[29] and river bottoms to preclude erosion and speed up ecological recovery. The chief purpose of this project is to restore anadromous stocks of Pacific Salmon and steelhead to the Elwha River, which take been denied admission to the upper 65 miles (105 km) of river habitat for more than than 95 years by these dams. Removal of the dams was completed in 2014.

Come across too [edit]

- Madison Creek Falls

- La Button Beach

- Blood-red Beach

- Rialto Beach

- National Annals of Historic Places listings in Olympic National Park

- Listing of national parks of the Usa

References [edit]

- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Partitioning, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-07 . (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ "Annual Visitation Highlights". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "Olympic National Park: Directions". National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-eleven-11 .

- ^ "The Economic system of the Olympic Peninsula and Potential Impacts of the Draft Congressional Watershed Conservation Proposal" (PDF). Headwaters Economic science (Bozeman, Montana). p. half dozen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-11-11 .

- ^ National Geographic Guide to National Parks of the United States (7th ed.). Washington, DC: National Geographic Social club. 2011. p. 402.

- ^ "Park Newsletter July/August 2009". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- ^ "Proclamations and Orders Relating to the National Park Service - Mountain Olympus National Monument" (PDF). National Park Service. March 2, 1909. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2016. Retrieved Oct 24, 2016.

- ^ "The National Parks Alphabetize 2009–2011". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- ^ "Olympic Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- ^ Landers, Rich (December 7, 2016). "Olympic Wilderness re-named for Sen. Dan Evans". The Spokesman-Review . Retrieved Baronial 18, 2017.

- ^ Ollikainen, Rob (Baronial xviii, 2017). "Ceremony marks alter of name to Daniel J. Evans Wilderness". Peninsula Daily News . Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "Foundation Document Overview Olympic National Park" (PDF). National Park Service History. National Park Service. Retrieved xi May 2021.

- ^ "Olympic National Park: Coast". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-08-23 .

- ^ "Metropolis of Sequim". Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Sequim, WA". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- ^ "U.Southward. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions)". Data Basin. Retrieved 2019-07-15 .

- ^ "Cougar alarm". Kitsap Lord's day (17 May 1992). Archived from the original on 9 Jan 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Mountain Goats in Olympic National Park: Biology and Management of an Introduced Species". National Park Service. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Bolsinger, Charles L.; Waddell, Karen Fifty. (December 1993). Expanse of Sometime-growth Forests in California, Oregon, and Washington. Resource Bulletin. Vol. PNW-RB-197. Portland, OR: U.Due south. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. hdl:2027/umn.31951d02996301m. OCLC 31933118.

- ^ "Paradise Burn - Incident Overview". inciweb.nwcg.gov. Incident Information Arrangement - National Park Service. September 3, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". U.s. Section of Agronomics. Retrieved 2019-07-15 .

- ^ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". world wide web.prism.oregonstate.edu . Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ "Olympic National Park Timeline - Olympic National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov . Retrieved 2017-10-16 .

- ^ "Olympic National Park Headquarters - Port Angeles WA". Living New Bargain . Retrieved 2021-08-06 .

- ^ Setzer, Christopher (July 16, 2019). "Olympic National Park". HistoryLink . Retrieved Nov 26, 2021.

- ^ Lien, Carsten. Olympic Battlefield: The Power Politics of Timber Preservation.

- ^ "Boating - Olympic National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov . Retrieved 2021-11-06 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Line-fishing - Olympic National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". world wide web.nps.gov . Retrieved 2021-xi-06 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Elwha River Restoration Project | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov . Retrieved 2022-03-04 .

External links and literature [edit]

- Official website

of the National Park Service

of the National Park Service - "The Pacific Northwest Olympic Peninsula Customs Museum". Academy of Washington. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- "The Evergreen Playground Online museum". University of Washington. Retrieved 2011-07-08 .

- Olympic National Park Documentary produced by Total Focus

DOWNLOAD HERE

Rain Gear Advice for Olympic National Park in Summer UPDATED

Posted by: dorisquichaved.blogspot.com

Comments

Post a Comment